‘Distance learning’, or ‘remote learning’, is a form of remote education that does not involve regular face-to-face contact between teacher and student or among students. Distance learning courses vary from occasional lessons to full courses taught through distance learning. This post outlines some tips for effective distance learning in the context of secondary education.

Jonathan Beale, Researcher-in-Residence, CIRL

1. Where possible, go with familiar and user-friendly educational technology

While students are often extremely proficient with the latest technology, it’s advisable, where possible, to opt for the educational technology students are most familiar with, is most user-friendly, and you know is readily available. Change often causes disruption; the less disruption, the better.

For videoconferencing, Zoom and Microsoft Teams are particularly effective for distance learning. Like all videoconferencing platforms at the moment, both are receiving high usage and consequently users can experience intermittent connectivity. So it’s sensible to have a primary and secondary option, such as both of these.

Some programs offer straightforward forms of communication that function as easy substitutes for email and are not a significant departure from the familiarity and ease of email. For example, Microsoft Teams has a ‘chat’ function which offers a useful means of communicating with students; this is especially convenient if it’s already being used for videoconferencing.

Schools often use certain programs as part of their approach towards digital learning, such as Microsoft OneNote. It’s probably best to stick with the school’s usual digital platforms as much as possible, for ease of familiarity, consistency and communication. Most importantly, you’ll know that students have access to the usual platforms, as long as they have connectivity.

2. Backup resources and work for students, in case of technological issues

Online distance learning requires a decent internet connection for all parties involved, particularly if using software where multiple students occupy a digital class (e.g., in Microsoft Teams). It may be the case that some students have poor connectivity and are only present in the class intermittently.

Foreseeing this possibility, it can be helpful to have teaching resources and learning tasks prepared, available online and circulated to students ahead of online class environments, which can be used if students experience connectivity problems. Some such resources and tasks could also function as extension work, so even those students who don’t experience connectivity issues could make use of the resources.

3. Backing up work

With a lack of physical resources, students need to ensure they get into the habit of regularly backing up their work. While digital devices nowadays typically offer to backup a user’s data as a matter of course (e.g., through iCloud on Apple devices), it’s sensible for students to take additional measures to backup their work in a safe place on the ether, such as Microsoft OneDrive or Dropbox. This is the responsibility of students; but it’s prudent to give students clear instructions on the importance of this.

Best Practices for Teaching Online (image courtesy of Arizona State University)

4. Feedback

Collaborative documents enable quick digital feedback and allow the teacher to keep up to date in real time with students’ completion of work. These are offered in many programs, such as OneNote, Dropbox and Google Docs. In OneNote, for example, students can submit work into their own area which only they and the teacher can see; the teacher can mark their work and the student can see the marking, without the requirement of email communication.

While email functions as a means of delivering feedback, it has significant limitations. ‘Track Changes’ in Microsoft Office offers a facility where a teacher can provide feedback on documents such that the student can see all of the feedback they’ve received, can accept or reject changes, and can respond to changes so the teacher can see how they’ve responded to feedback.

5. The additional time students might have when working from home

For many students, school days are jam-packed with curricular and co-curricular activities, including sports, clubs, music lessons and other commitments, as well as social time. With people worldwide currently being increasingly advised or required to stay at home, for some time students will not participate in many typical school activities such as clubs or sports; those students taking one-to-one lessons outside of their academic subjects such as music lessons will have such lessons temporarily suspended; and there won’t be the usual social time with friends.

Many students are therefore likely to have time available which they do not usually have, some of which could be used for extension work in their academic subjects; and some students may wish to fill much of that time completing extension work. So, teachers might wish to offer more extension work and optional extension work than usual to alleviate the possibility of students spending a significant amount of time with little to do.

Given the amount of time students spent completing work digitally, teachers might wish to set some non-digital work, to lessen the possibility that students are working from digital devices all the time. Exercises such as hand-written tasks, reading books or practical exercises keep students working on challenging tasks while away from digital devices.

Such exercises can also provide students with a wider variety of learning tasks. Extension work is best set not as a continuation of the same task, but as work designed to stretch and challenge students in a variety of ways; so varying the tasks with non-digital exercises complements the aims of effective extension work.

6. Regular contact

If possible, it’s good to set up regular videoconference calls with students in group settings, and state particular times of the week where email contact would be best for quick correspondence. Digital ‘office hours’ can be effective. During such periods, students know that teachers will be available and know that this is a particularly appropriate time to correspond via email with questions which can be addressed quickly, and can perhaps call teachers via videoconference.

Zoom allows users to set up ‘meetings’ with groups, where students can be sent invites from the meeting’s host (i.e., the teacher) and can join the videoconference meeting. An ‘office hour chat’ could be set up, which all students from a particular class could join through videoconferencing.

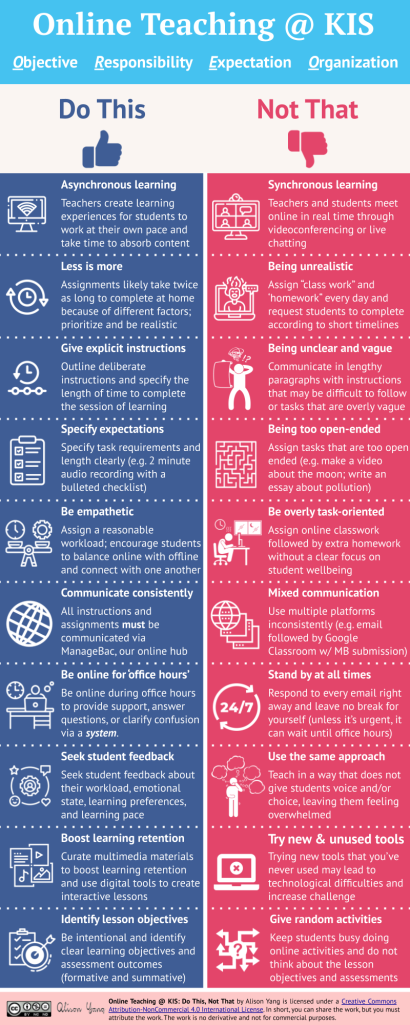

Online Teaching @ KIS: Do This, Not That, by Alison Yang

7. Fletcher-Wood’s advice on distance learning

An excellent blog post written last week by educational researcher Harry Fletcher-Wood, ‘Learning in the time of coronavirus: planning distance learning’, offers detailed advice on how to address some key challenges teachers face with planning and conducting effective distance learning. He identifies several challenges schools face in distance learning and offers suggestions for addressing them. His six main recommendations are:

1. Identify what matters most in teaching now and find new ways to do it through distance learning.

2. Set simple tasks which students can get used to doing well.

3. Share, as soon as possible, what you want students to do and why you want them to do it.

4. Check student understanding.

5. Pick simple educational technology solutions.

6. Help students to form effective learning and work habits.

Recommended further reading and references

Some of the following are concerned solely or primarily with higher education, since distance learning is more common in higher than secondary education. But some of the strategies can be applied in secondary education, in some cases with the necessary adjustments made.

- An article published in The Conversation yesterday by Kyungmee Lee on ‘14 tips for better online teaching’

- Stanford University’s article on ‘Ten Best Practices for Teaching Online’, which is the third chapter in J. V. Boettcher and R-M. Conrad, The Online Teaching Survival Guide: Simple and Practical Pedagogical Tips (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010).

- The Office of Distance Education and eLearning at Ohio State University offers an overview of teaching strategies for distance education.

- Chief Learning Officer offers five strategies for effective distance learning.

- The Center for Research on Learning and Teaching at the University of Michigan has a set of resources providing guidance on effective distance learning.

- The January 2019 issue of Impact: Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching is on Education Technology and contains many articles pertinent to distance learning, including articles on independent digital learning, dialogic learning in Google Classrooms and effective digital feedback.

- A 2013 article by Andrianes Pinantoan provides guidance for conducting distance learning effectively, including a section on how to conduct correspondence courses effectively – i.e., those courses that consist in correspondence between teacher and student, such as email correspondence, and a section on instruction strategies for distance learning.

- A potential issue that arises from distance learning is students feeling isolated. Nicholas Croft, Alice Dalton and Marcus Grant have written an article on how to overcome isolation in distance learning.

- Jean Dimeo’s 2017 Inside Higher Ed article, ‘Take My Advice’, summarises guidance for teaching an online course taken from 17 instructors.

- Arizona State University published a useful article in 2018 on the ‘Best Practices for Teaching Online’.

Teacher Tapp has offers several recent blog posts on distance learning:

- ‘Will schools cope with a coronavirus closure?’, 9 March 2020

- ‘Monitoring COVID-19 readiness in schools’, 12 March 2020

- ‘A Difficult Week: What you’ve told us about how Coronavirus is changing school life’, 16 March 2020

Other useful references:

Al-Arimi, Amani Mubarak Al-Khatir, 2014. ‘Distance Learning’. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences 152 (2014), 82-8.

Filcher, Carol and Greg Miller, 2000. ‘Learning Strategies for Distance Education Students’. Journal of Agricultural Education, Vol. 41, Issue 1, pp. 60-8.

Gill, T. G., 2004. ‘Distance learning strategies, Part 2: A Macro Analysis’. E-Learn Magazine.

Gill, T. G., 2004. ‘Distance Learning Strategies that Make Sense: A Micro Analysis’. E-Learn Magazine.

Pinantoan, Andrianes, 2013. ‘Conducting Distance Education Effectively’. InformEd.

Roddy, C., D. Lalaine Amiet, J. Chung, C. Holt, L. Shaw, S. McKenzie, F. Garivaldis, J. M. Lodge and E. Mundy, 2017. “Online Learning: Critical factors” in ‘Applying Best Practice Online Learning, Teaching, and Support to Intensive Online Environments: An Integrative Review’, Frontiers in Education: Digital Education.