This week’s blog post is based on Chapter Two of Jared Cooney Horvath and David Bott’s book entitled 10 Things Schools Get Wrong: And How We Can Get Them Right. This chapter formed the basis of this week’s Teaching and Learning Reading Group, based here at Eton.

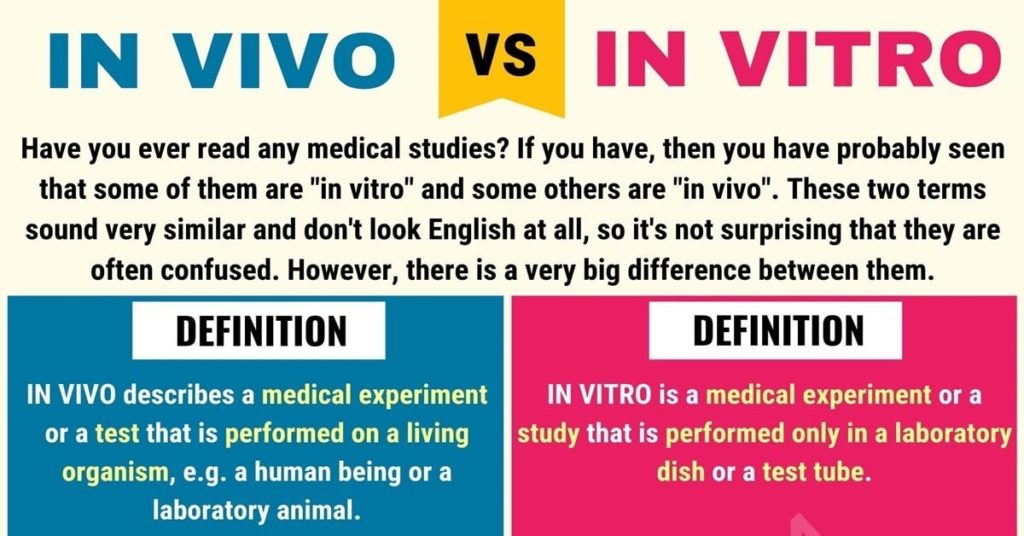

This chapter discusses the issues surrounding evidence and the problem with how it is translated in an educational setting. Horvath and Bott open with an example of the way in which medical researchers approach experiments: ‘in vitro’ and ‘in vivo’.

According to Dowden and Munro (2019), 90% of experiments carried out in vitro become harmful or inert when carried out in vivo.[1] This is also true of the reverse: when experiments are initially carried out in vivo, they can produce an adverse result when conducted in vitro.

Horvath and Bott use this medical analogy to argue that although laboratory data may inspire or influence teachers on how to approach certain situations, it should never directly drive teaching practice. They claim that this is because of ‘perceptive translation’, where data is used from one field and applied to another without taking into consideration all of the possible effects.

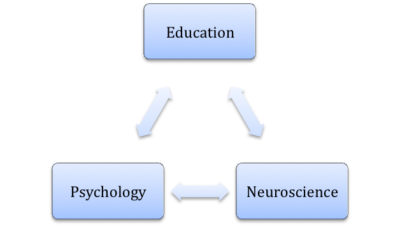

These new properties can be problematic, especially when they trigger unintended and unpredictable consequences for the experiment. If we apply this to the schoolroom, then we can see how moving from neuroscience to psychology and subsequently education, can give rise to new properties.

Horvath and Bott give an example of this in an educational setting with the 2016 study conducted by UWA. Based on studies from neuroscience, this university decided to offer their students ‘brain food’ in the form of jelly beans (Mergenthaler et al., 2016).[3] This decision was made on the basis that the brain runs on glucose and will function quicker when supplied with sugar. However, when the brain is overloaded with sugar it also becomes scattered, hyperactive, movements become dyskinetic and emotions become volatile.[4] When multiple individuals consume sugar simultaneously in a social setting, interactions between individuals become chaotic, communication becomes disjointed and social norms are often compromised.[5] Therefore, despite the benefits of glucose on brain activity, the emergent properties hindered the overall learning as a result.

To avoid this, ideas from one level of organisation have to be redefined, adapted and retested at each subsequent level to account for these emergent properties.

In education, the experts redefining, adapting and retesting these ideas, should be the teachers themselves.

The chapter continues with Horvath and Bott proposing that teachers should also systematically document these attempts to translate evidence into the context of education and their own teaching. By doing so, they can help to establish a shared body of knowledge which is one of their recommendations from Chapter One. Collecting and organising information in regards to the impact of varied practices in their classroom is essential if we are to be respected as a profession.

Finally, Horvath and Bott end by claiming that consistency in presenting and disseminating this work amongst practitioners is essential. As in the medical profession, they propose a centralised approach, where teachers adhere to universal guidelines on how to organise their work and this work is made available via a central repository.

How can we translate research from different fields?[6]

• Use a high quality and trusted knowledge repository, such as Impact, to provide clear summaries of effective interventions.

• Look for evidence with a similar context i.e. conducted in independent boys’ boarding schools.

• If similar contexts cannot be found, spend some time thinking about how the evidence can be contextualised for your individual situations.

• If you can, use intermediaries- such as a Researcher-in-Residence or Research Lead- to help translate evidence into tools for implementation in the classroom.

• If possible, try to work directly with academics and researchers, in order to gain a better understanding of, and implementation of, evidence.

Adapted from the NFER Report Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why? (2014).

[1] H. Dowden & J. Munro, ‘Trends in Clinical Cuccess Rates and Therapeutics Focus’, (2019), Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, Vol. 18, pp. 495-496.

[2] M. A. Bedau & P. E. Humphreys, Emergence: Contemporary Readings in Philosophy and Science, (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008).

[3] P. Mergenthaler, U. Lindauer, G. A. Dienel & A. Meisel, ‘Sugar for the Brain: The Role of Glucose in Physiological and Pathological Brain Function’, (2013), Trends in Neurosciences, Vol. 36, pp. 587-597.

[4] C. R. Freeman, A Zehra, V. Ramirez, C. E. Wiers, N. D. Volkow & G. J. Wang, ‘Impact of Sugar on the Body, Brain, and Behaviour’, (2018), Frontiers in Bioscience, Vol. 23, p.2255.

[5] D. Benton, A. Maconie & C. Williams, The Influence of the Glycaemic Load of Breakfast on the Behaviour of Children in School, (2007), Physiology & Behaviour, Vol. 92, pp.717-724.

[6]Julie Nelson & Clare O’Beirne, NFER Report: Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why? (2014), Available:<Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why? (nfer.ac.uk)> Accessed: 14 October 2021.