Jonathan Beale, Researcher-in-Residence, CIRL

Just over a week ago, an early Renaissance painting by the Florentine painter Cimabue set a new record as the most expensive medieval painting ever sold, fetching over €24 million at an auction in Actéon in Senlis, north of Paris. Cimabue’s 13th-century Christ Mocked was recently discovered hanging above the hot plate in the kitchen of a nonagenarian woman in Compiègne, France. She had an auctioneer visit the house when she decided to sell it and some belongings. The auctioneer, Philomène Wolf, said in an interview with La Parisien that upon noticing the painting, she ‘immediately thought it was a work of Italian primitivism’. Wolf took the painting to an Old Master appraiser in Paris, Eric Turquin, who estimated it could auction for between €4 million and €6 million.

Turquin believes the painting is part of a polyptych by Cimabue, which also includes the Flagellation of Christ, in the Frick Collection in New York, and Madonna and Child Enthroned between Two Angels, in London’s National Gallery. Among the evidence behind Turquin’s theory is that there’s a matching pattern of larvae tunnels across the three works and he believes the poplar panel on which Christ Mocked is rendered is the same as the other paintings.

This story illustrates at least three levels on which Christ Mocked can be experienced. The painting’s owner probably experienced it as a beautiful painting. Wolf saw that it was a work of Italian primitivism. Turquin identified the work’s role as part of a late 13th-century polyptych by Cimabue.

Wolf and Turquin are able to experience Christ Mocked in these additional ways due to their expert knowledge of subjects such as art history and art valuation. Their proficiency in such subjects enables them to identify certain features of Cimabue’s painting and place them within the conceptual schemes associated with such subjects.

We can be taught to experience in the world in the ways in which Wolf and Turquin experience Cimabue’s painting. Enabling us to have richer experiences of the world in ways such as these is one of the means through which education can bring us happiness.

Education has many aims. It has epistemic aims, such as imparting knowledge and developing students’ understanding of various subjects and areas of life. It has moral and political aims, such as developing moral and civic virtues, to help students become virtuous citizens able to contribute to society and live good lives. Education also has a more fundamental aim, which is arguably its most important: to increase happiness, both for the individual receiving education and for the respective society as a whole.

There are several means through which education can do this. The most obvious is that education provides access to a better quality of life, through increasing an individual’s access to their desired career and to higher earnings. A less obvious way is that education enables one to have a richer experience of the world. By ‘richer’, I mean that by gaining knowledge or understanding of some field of inquiry, one is able to experience more aspects of that field. Education can also teach us skills that enable us to experience the world in new ways. By opening up the world, we have access to more things that can bring about happiness.

The philosopher and influential educationalist Mary Warnock held that the point of education is pleasure. In a BBC In Our Time podcast on ‘Education’, Warnock argues that education ‘opens up enormous possibilities’, such as understanding and manipulating the world. Education can provide us with the ability to perceive, conceptualise and understand things we would not otherwise be able to. It provides us with the ability to experience more aspects of the world.

This is true for all disciplines. Historical knowledge and understanding provides one with the ability to recognise the significance of certain historical artefacts or figures within a particular period and history as a whole, cognitively placing the artefacts within a conceptual framework and an historical narrative. One is likely to have a far richer experience of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, for example, if one possesses knowledge of its historical significance both as the former seat of the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople and later as an imperial mosque in the Ottoman Empire. Similarly, a greater knowledge and understanding of jazz provides one with the ability to identify and appreciate musical features common to jazz on a deeper level of detail. The aesthetic features one can discern from receiving an education in jazz could include the way a saxophonist develops an improvised solo; a rhythm section’s use of polyrhythms; the ‘feel’ that emerges through a musician’s playing; or the nuances that give the finest jazz musicians their distinctive musicianship.

An example of the richness of an experience as a result of greater knowledge in a particular field can be found in Eric Lomax’s The Railway Man (1995). As well as articulating the limitless possibilities of human forgiveness, in the book, Lomax, a fervent and extremely knowledgeable trainspotter, illustrates how such knowledge can make that hobby typically regarded as exemplifying the archetypal vocation of an anorak sound incredibly exciting, thanks to the fervour with which he recollects his experiences and the wealth of knowledge of locomotives he demonstrates. One of Lomax’s recollections is of seeing a rare locomotive while docked in Cape Town during the Second World War:

… I wandered off one afternoon and headed, inevitably, for Cape Town railway station, an addict hoping for a surprise. … I certainly got my surprise. On a plinth in the station was an ancient locomotive, a small tank engine built by Hawthorns & Co. in Leith in 1859. It was the first locomotive ever to work in the Cape Colony, and was probably the oldest surviving Scottish engine in the world. … It was a lovely old tank engine, a beautiful piece of machinery on fragile ungainly wheels with surprisingly delicate coupling rods. … I admired it in the middle of that hot African station for a long time.[1]

Most of us, upon seeing this tank engine, would just admire an antiquated, beautiful object; but Lomax is able to identify the historical significance both of the locomotive and the various inventions that constitute its parts, and place them all within the history of locomotive engineering. He is able to discern the engine’s parts and their functional roles. His knowledge enables him to identify the concepts associated with locomotives and situate them within a conceptual scheme, identifying the conceptual connections. Such knowledge enables Lomax to have a far richer experience of this object than most of us.

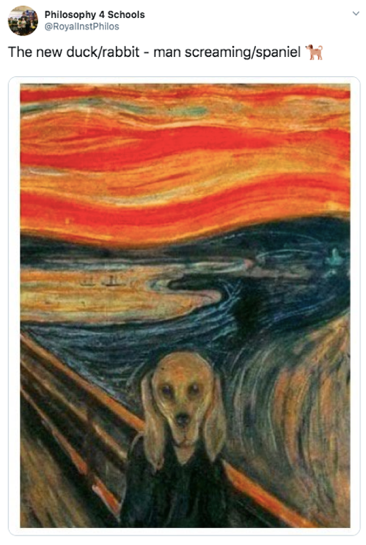

The way that education can enable us to have richer experiences of the world can be elucidated through an idea in the philosophies of Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein, sometimes described as ‘aspect perception’. Human beings are able to ‘disclose’, to use Heidegger’s term, the world in certain ways as a result of our distinctive cognitive capacities. One example of ‘seeing aspects’ used by Wittgenstein and Thomas Kuhn was given in an earlier blog post: seeing the image of a duck-rabbit as either a duck or a rabbit. Or, to use a recent amusing example shared on Twitter by the Royal Institute of Philosophy’s ‘Philosophy in Schools’ program: seeing a memetic depiction of Edvard Munch’s The Scream as either a person screaming, or a spaniel:

A cat can see a chair as a desirable place to take a nap. But we are able to situate a chair within a conceptual scheme of furniture and understand its relation to other items of furniture; we can describe a chair in terms of its ergonomic, aesthetic, cultural and historical features. We can recognise a chair’s significance as an antique or an heirloom, or see how it would make a lovely addition to the lounge.

Education enables us to disclose more aspects of the world. Greater knowledge of botany enables a gardener to see more possibilities for cultivating a garden; greater knowledge of ornithology enables a bird watcher to identify the distinctive murmurations of bird species; and an education in psychology provides a psychologist with enhanced means of reading the psychological causes behind human behaviour.

In these and similar cases, one is able to conceptualise some aspects of the world on a more detailed level, thanks to greater knowledge and understanding of a particular field. Lomax can see aspects of locomotives and Turquin can see aspects of Cimabue’s work most of us cannot.

John Stuart Mill argued that education would increase the general amount of happiness in society. Mill used this to argue for universal education on moral grounds. His argument reflects the normative ethical theory he endorsed, utilitarianism, which holds that the right actions are those that bring about the best consequences, such as the greatest overall happiness or pleasure. According to utilitarianism, morality’s aim is to improve our lives by increasing the amount of goodness in the world. Mill argued that a more educated society is one that can experience a greater amount of happiness.

Education does not open up the space for only good experiences, though. Possessing greater awareness of the problems of the world can also bring about sadness. While we would regard an education in history as impoverished if it didn’t include at least some study of what genocide is and what the common causes of genocides throughout history have been, the knowledge gained is likely to bring about at least as much sadness as happiness; indeed it arguably should, since an important part of character education is to cultivate empathy in students.

But that is a small price to pay for the intellectual and experiential gains one makes from learning. Even if we experience much sadness as a result of learning about the world, it’s surely better to be more knowledgeable with the risk that this might bring about some sadness. Or, as Mill put it, surely ‘It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’.[2]

[1] Eric Lomax, The Railway Man (London: Vintage, 1995), pp. 52-3.

[2] John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (Second Ed.; edited by George Sher) (Cambridge: Hackett, 2001 [1861]), Ch. II, p. 10.