This blog post is based on a journal article written by Christopher Ellis, a Geography master at Eton College, and describes an action research project he conducted at a previous school. The project looks at the use of enquiry-based learning in developing Year 8 Geography students’ understanding of place and migration, with particular reference to the ongoing refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East. The full journal article can be read here.

A key aspect of this project was the consideration of the advantages and challenges of enquiry-based learning: specifically, how enquiry relates to issues of misconception and representation in Geography and how the application of enquiry-based learning can shift students’ understandings of place away from self/other orientalist mentalities and towards a more nuanced one (Massey, 2004).[1]

Enquiry, according to Roberts (2013a), refers to a range of approaches in which “students are actively engaged in investigating questions and issues”.[2] It encourages a questioning attitude, develops students’ understanding of a range of data and sources of evidence, prompts them to justify their positions using evidence, challenges misconceptions, and fosters their critical thinking skills.

The subject of this enquiry – the European refugee crisis – is considered to be a controversial issue. However, this does not mean it should be avoided. There are significant advantages to exploring controversial issues in schools as they allow students to understand the complexity and connectedness of the world, grasp the influence of past decisions on the present, and can help guard against indoctrination (Roberts, 2013b).[3] In sum, there are huge advantages to teaching the topic of migration through the lens of an enquiry focused on the controversial issue of refugees.

The Project

To inform students’ understanding of place and migration, case studies on the Syrian-European refugee crisis were used. These case studies were presented to a class of Year 8 students through a five-lesson sequence which focused on the enquiry approach and was taught at the beginning of a new unit on migration.[4]

Lesson 1: The first lesson in the sequence was entitled ‘Are we a nation of migrants?’. The purpose was to move students away from a possible misconception of migration as a process that distant others ‘do’ to the UK externally. Rather, students were challenged to think of migration as a process which has defined, and continues to define, the UK as a place and people.

Lesson 2: This lesson introduced the refugee crisis, with a key focus on its representation in the media. This lesson had two purposes. First, inspired by Bolton (2008), students were to learn the importance of founding any viewpoint on a controversial issue in empirical evidence. Second, moving beyond this, they were to learn how to think critically about evidence.

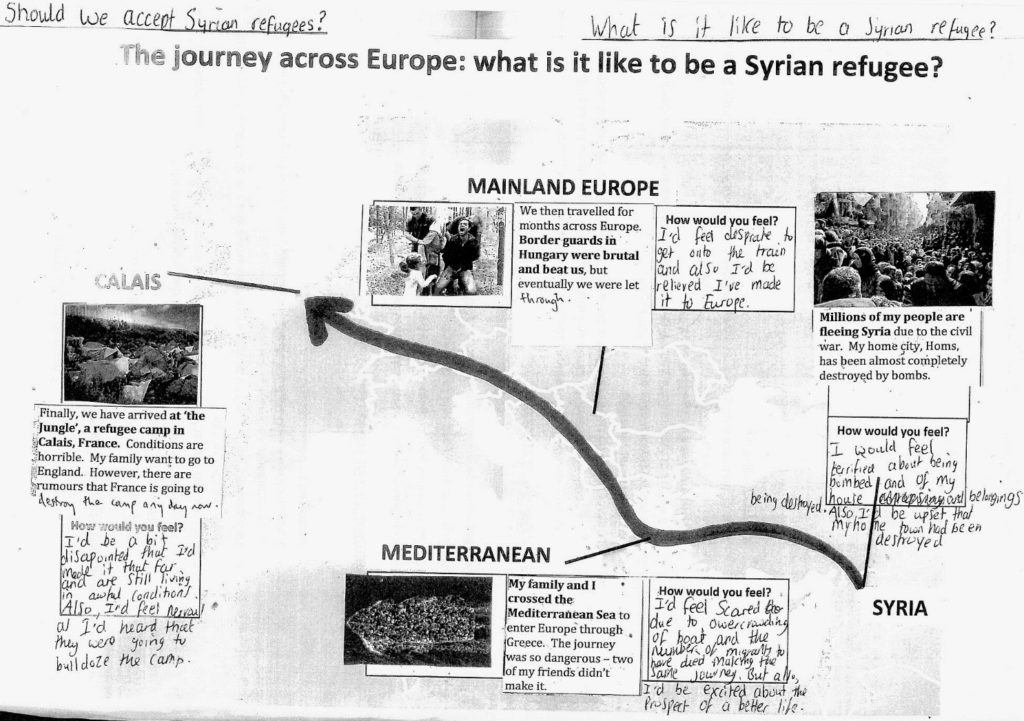

Lesson 3: This lesson was entitled ‘What is it like to be a Syrian refugee?’ and used empathy as a device for developing students’ sense of connection to Syrian refugees. It used real-life mobile phone footage to document four stages of a child refugee’s journey, from war-torn Syria to the Jungle refugee camp in Calais. Following Spitieri (2013), it was hoped that empathy would be key in shifting students’ attitudes about migrants, fostering their sense of connection between near and distant places.[5]

Lesson 4: The penultimate lesson consisted of a debate in which students discussed their varied answers to the enquiry question, ‘Should we accept Syrian refugees?’. They were to apply all learning through the sequence to debate different positions as a model UK Parliament.

Lesson 5: A final lesson was set as cover work in which students wrote a letter to their MP outlining and explaining their closing positions. Combined with a debrief questionnaire, the lesson provided plenary data for analysing their views at the end of the sequence.

Findings: How did enquiry-based learning support students’ understandings of the European refugee crisis, and the concept of migration more widely?

Engagement

Reflecting back on the project, it appeared as though students were very highly engaged throughout the enquiry sequence. Indeed, students seem to be more invested in contemporary issues when given the space to voice, debate and justify their views. Focusing an enquiry question around a current issue, which related to their lives as young British citizens, gave students a ‘need to know’ sense of urgency (Roberts, 2013a), created a lively debate, and made them curious to seek further answers.[6] This was clearly indicated by the range of responses to the second question on the closing questionnaire, which invited students to mention anything they would still like to know about the refugee crisis.

Curiosity

The most popular requests for information from these questionnaires related to the Syrian conflict itself. Their curiosity centred on the reasons behind the crisis, how long it has lasted and its prospects for the future; the perspectives of other European countries involved in the crisis; and more about the lives of Syrian refugees as they cross the continent (“How do they get food and water?” for example). Indeed, one higher attaining student’s response (“Why do they have to have papers forged when they are fleeing from conflict?”) demonstrates the potential of enquiry-based learning to support very high-level thinking.

Empathy

Empathy building was clearly a successful strategy for developing students’ learning about the refugee crisis. When asked in the closing questionnaire about their learning, the most common response across the attainment range mentioned the hardships faced by refugees in their journey to cross Europe. This indicated the particular success of Lesson 3, in which they completed emotive maps (Figure 1) based on real-life footage of the journey. Empathy building was therefore successful in fostering students’ sense of connection between far and near places. Indeed, those who changed their positions on the refugees from unsympathetic to sympathetic cited empathetic reasons for doing so. More broadly, this reveals the importance of teaching controversial issues in order to guard young people against indoctrination (Roberts, 2013b).[7]

Top Tips for integrating more enquiry-based activities into your own lessons

- Consider how aspects of course content can be framed around enquiry questions.

Enquiry-based learning stimulates critical thinking, deepens student engagement, and opens up opportunities for empathy-building. Therefore, it may lead to improved academic outcomes in the context of knowledge-heavy, ‘dry’ exam specifications.

- Try to deepen students’ understanding of controversial topics by encouraging them to engage with their own life experiences.

A surprising outcome of this project is that over the course of the lesson sequence, some of the most unsympathetic views towards refugees were expressed from minority ethnic students who were not born themselves in the UK?. Self-reflection may have helped to deepen their understandings of these issues and encourage them to empathise more.

- Encourage students to use subject-specific vocabulary when explaining their views in discussion.

Although enquiry-based learning approach can be successful in developing students’ understanding of certain concepts, they also need to be reminded to make use of the correct subject-specific terminology. For example, in this project, students could speak extensively about their views on migration but very few students drew upon migration vocabulary in explaining their views at any stage of the sequence. Notably, they rarely drew upon concepts such as push and pull factors, nor the distinctions between economic and forced migration, asylum seeker or refugee.

- Minimise teacher intervention in student discussion to avoid influencing them with your own biases.

When discussing controversial issues, energy levels in the room can sometimes become too high and hyperbolic statements from students often go unchallenged by their peer group. Students should be aware of different perspectives and teachers can intervene if the discussion becomes too inflammatory but they should also refrain from imparting their own views too heavily.

- Concept-mapping techniques are an easy way for learners to explore the complexity of any topic by focusing learners on the connections between pieces of information.

They could prompt learners to think more deeply about a contemporary issue, a policy, a moment in history, a scientific problem, etc.

[1] D. Massey, ‘Geographies of Responsibility’, Geografiska Annaler Series B: Human Geography, (2004) Vol. 86, pp. 5-18.

[2] M. Roberts, ‘The Challenge of Enquiry-based Learning’, Teaching Geography, (2013a), Vol.38, pp. 50-52.

[3] M. Roberts, ‘Controversial Issues in Geography’ in Geography Through Enquiry, (London: GA Publishing, 2013b), pp. 116-117.

[4] R. Yin, Case Study Research: Design and Methods, (California: Sage, 2003).

[5] A. Spitieri, Can My Perceptions of the “Other” Change? Challenging Prejudices Against Migrants Amongst Adolescent Boys in a School for Low Achievers in Malta, Research in Education, (2013), Vol. 89, pp. 41-60.

[6] M. Roberts, ‘The Challenge of Enquiry-based Learning’, Teaching Geography, (2013a), Vol.38, pp. 50-52.

[7] M. Roberts, ‘Controversial Issues in Geography’ in Geography Through Enquiry, (London: GA Publishing, 2013b), pp. 116-117.