This week’s blog post is a guest post written by Gill Little, Deputy Head for Teaching and Learning at Queen Anne’s School

My experience of remote teaching so far is that it feels like normal teaching on steroids! Everything seems to be exaggerated. I feel more exposed and need to be really on top of my game. I also feel that there is a danger of my classroom being ‘open all hours’. That said, I feel an excitement about the remote learning experience and how it has invigorated pedagogic discussions around good practice.

Having had some time to reflect on my own remote teaching experience, the following are some pieces of advice I would like to share to help support the delivery of quality remote teaching and learning.

Image courtesy of Medium

Be prepared

Being ill-prepared leads to time wasting; this seems even more the case when teaching through videoconferencing and there is a danger that the students are more likely to ‘switch off’.

Be time aware

Don’t try to cram too much into your lessons and give yourself and your students a short break between lessons. In school, students have time between lessons to move to the next lesson; this can give them and teachers a short break between lessons. Plan your remote teaching to include such breaks, too, by finishing your active teaching about 5 minutes before the end of the lesson.

Don’t overestimate the amount of work that can be completed by students

Avoid giving students too much work to complete during lessons and to finish off outside of lessons. Students who work at a slower pace may quickly become overburdened and anxious.

Be aware of cognitive overload and underload

The working memory has a limited capacity and is easily overloaded. If a student’s working memory is overloaded, their perception and ability for higher order thinking decreases. So, as with normal lesson preparation, when planning and delivering remote teaching, ensure that what you have planned avoids overloading a student’s working memory.

This can be achieved by reducing extraneous cognitive load: the load generated by the way that material is presented and the nature of instruction. Extraneous load does not support learning. To reduce this, it helps to try to keep to a minimum the amount of information being used or addressed at any one time. It can also be achieved by managing the amount of intrinsic cognitive load effectively: this is the inherent difficulty of the teaching and learning material , which can be influenced by prior knowledge of the topic being studied. Intrinsic cognitive load can be managed through, for example, effective modelling and scaffolding.

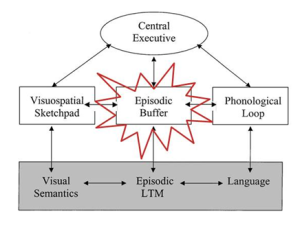

Additionally, consider using dual-coding techniques – i.e., presenting information through more than one sensory means, such as both visually and phonologically. The effectiveness of working memory improves when information is dual-coded. So, for example, rather than just talking to the class, try and use visuals such as annotated diagrams.

The diagram below illustrates how dual coding from the ‘inner voice’ and the ‘inner eye’ work collaboratively. It is based on Baddeley’s model of the working memory.[1]

Baddeley’s model of the working memory (image courtesy of Working Memory)

To avoid overloading working memory, consider using retrieval practice techniques: strategies to encourage students to store and retrieve information from their long term memory, as this reduces the demands on the working memory and develops their fluency in recall. The good news is that the capacity of the long-term memory is almost limitless!

On the other hand, the working memory can also be underloaded. If underloaded, you risk students becoming easily bored and less engaged, and you will lose their attention. The issue of boredom can be more problematic in the remote learning environment, as you cannot readily monitor their screens or other distractions that they might have.

Therefore, try to reach the ‘goldilocks zone’ when planning lessons: the sweet spot where the work you set has the desirable level of difficulty that will engage the students but not overburden them.

Adapt key principles of teaching and learning for the remote context

When teaching online environment, far fewer non-verbal cues are available, if any. So it is more difficult, if not impossible, for the teacher to read body language and to survey the classroom to pick up cues from students and respond accordingly.

This issue can be alleviated by adapting some key principles of teaching and learning for the remote context and applying them. Many key principles of teaching and learning cannot be applied to the same extent or in the same ways in remote contexts as they are in the classroom. But they can be adapted for an online environment.

In what follows, ten adapted key principles are outlined.

1. Set a positive tone to lessons

A positive tone clearly underlies the success of any lesson. In a remote learning setting, students are even more dependent on the teacher’s positively and enthusiasm than in the classroom.

Try to break through the barrier of the computer screens by ‘over-egging’ the behaviours you normally employ to engage positively with students. This is vital at this time, as students are feeling isolated and need to know that you care.

2. Make your lessons imitate what you normally do in the classroom

As far as is practicable, try to plan your lessons such that they imitate your usual classroom lessons, both in terms of routines and activities. This gives the students a sense of normality that they are missing in many other aspects of their lives.

Remember, also, that a classroom is a social and intellectual community, and by imitating that community online, you can support the development of an online community. This supports student engagement both with one another and with the teacher. (For more on this, see our earlier blog post.)

3. Make your explanations clear and coherent

It is riskier to rely on students to let you know whether or not they have understood in a remote learning environment, because far fewer non-verbal cues are available for interpreting students. Alleviate the risk that students have not understood by ensuring that your explanations are as clear and coherent as possible.

4. Make the most of opportunities to work in real-time

Make the most of every opportunity to work in real-time, as you do in the classroom. For example, demonstrate modelling and scaffolding techniques, illustrate examples and share notes using digital file sharing platforms, live. Good ways to do this online include the screen sharing facilities on Skype or Zoom (both of which are freely available online), sharable documents in Google Docs (also freely available online), and sharable digital whiteboard facilities (Microsoft OneNote is particularly good for this).

5. Allow students sufficient time to complete tasks

We can often underestimate this in the classroom and in the remote classroom it can be more difficult to ‘get around the room’ to support students by, for example, answering questions. You may need to allow students more time than in the classroom to complete tasks.

6. Include regular ‘pause points’ to encourage active participation and discussion

Regular pause points support formative thinking both in classroom and remote settings. For example, students can learn from one another through a discussion during a pause point, or students can use pause points to consolidate their understanding.

Digital collaboration spaces are excellent to use during pause points, as students can share ideas with one another and with the teacher. Google Docs and Microsoft OneNote both offer real-time collaboration spaces.

Pause points in a remote learning setting can also help to develop a culture of active engagement in the remote setting. Students should not just be present in the remote ‘room’, but actively engaging in the content of the lesson.

7. Build in opportunities for independent learning and creativity

Encourage opportunities to learn creatively and stretch and challenge opportunities that students could undertake independently. This seems even more important during this period of lockdown, as students will not be engaging in their routine co-curricular activities and so many students will have more spare time.

8. Reflect upon the ways in which you can provide effective and timely feedback

We all know about the importance of feedback, but also the time it can take. Try to avoid overburdening yourself with unnecessary marking by considering other forms of assessment that could be employed online. In particular, if working through videoconferencing you can assess work in real time, by providing feedback – written or verbal – on work that has been shared via email or viewable on a shared document.

Some shared document pages allow students to see the teacher’s comments in real-time – for example, Google Docs and Microsoft OneNote. OneNote allows teachers to comment on the work students are doing and has a ‘collaboration space’ where students can contribute their ideas, which enables peer assessment. This helps the teacher to check that students are on-task.

Alternatively, use mark schemes so that the students can mark their own work through self-assessment; this helps to build a culture of ownership and responsibility.

For more on methods of assessment in an online setting, including peer assessment and self-assessment, see our previous blog post.

9. Use regular, low-stakes testing

Regular, low-stakes testing helps to ensure that all students are ‘on track’. This can be conducted through, for example, starter activities and plenaries. This seems to be even more important in the remote learning setting, as there is a risk of some students becoming disengaged and falling behind.

10. Stay connected

Students do not currently have opportunities to ‘drop by’ for additional support. Provide students with opportunities to contact you for additional support that they might need. However, ensure that you give clear boundaries in terms of your speed of response, to preserve your own well-being.

One way to do this is to specify virtual ‘office hours’, during which you’re available for videoconference calls, or can quickly reply to emails, or in an online forum (Microsoft Teams offers a good platform for online forum-style discussion, where a teacher can be quickly available to reply to all students).

Gill Little is deputy head for teaching and learning at Queen Anne’s School. She has over thirty years of teaching experience. The first fifteen years of her career were spent teaching geography at Henley College, a tertiary college where she was the subject leader for ten years. In 2002, she became head of geography at Queen Anne’s School and she led the department until 2010. During that time, she developed a tracking and monitoring scheme that was rolled out through the school. She was promoted to assistant head (academic) in 2008 and later further promoted to director of teaching and learning, in which role she developed the tracking and monitoring scheme and undertook wider responsibilities in teaching and learning. In 2017, she became deputy head for teaching and learning.

[1] See Alan Baddeley, Working Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986) and Working Memory, Thought, and Action (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).