After a two-year hiatus, this week sees the re-opening of Eton’s School Library. Over the last two years, the library has been subjected to an intensive programme of remedial repairs to various ceilings and the Eton Community is delighted that the library is ready to be used once again by both masters and boys alike.

In many schools, however, the school library can be an underrated and underused resource. Therefore, this week’s blog post seeks to explore the role played by school libraries, and in particular their impact on students’ critical thinking skills and information literacy.

As access to information in the 21st century becomes increasingly ubiquitous, young people must possess effective information and literacy skills. Aldrich (2007) claims that these skills are necessary if they are going to be able to negotiate this digital landscape and think critically about the information they’re presented with.[1] The report by the Commission on Fake News and the Teaching of Critical Literacy Skills in Schools (2018), found that only 2% of children and young people in the UK have the critical literacy skills they need to tell if a news story is real or fake.[2] Therefore, the need to develop young people’s critical thinking skills is essential.

Barry Beyer (1995) defines the skill of critical thinking as “the ability to assess the authenticity, accuracy and/or worth of knowledge claims and arguments.”[3] In his study, Beyer lists a core group of competencies related to the acquisition of critical thinking skills.

These core competencies include:

• distinguishing between verifiable facts and value claims;

• determining the reliability of a source;

• determining the factual accuracy of a statement;

• distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information, claims or reasons;

• detecting bias;

• identifying unstated assumptions;

• identifying ambiguous or equivocal claims or arguments;

• recognising logical inconsistencies or fallacies in a line of reasoning;

• distinguishing between warranted or unwarranted claims; and

• determining the strength of an argument.

More recently, the Foundation for Critical Thinking has published their own list which describes a critical thinker as one who:[4]

- raises clear and precise questions;

- gathers, assesses, and interprets relevant information;

- derives well-reasoned conclusions, tested for relevance;

- is open-minded, evaluating assumptions, implications, and consequences; and

- effectively communicates solutions to complex problems.

Here at Eton, we aim to promote the best habits of independent thought and learning for boys, which includes critical thinking. The School Library is perfectly placed to support this and has developed an information literacy and research skills framework that can be used when boys undertake research. This framework includes skill descriptors for:

– Question comprehension

– Critical evaluation

– Note taking

– Managing information

– Critical analysis

– Presenting information

– Referencing skills

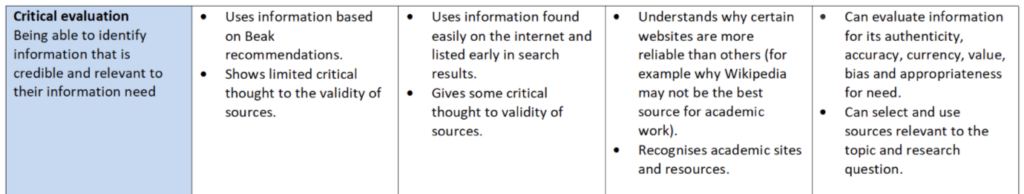

These descriptors are then split into four levels of competency and boys can build their skills by working along the framework.

Here is a sample of the descriptors for critical evaluation:

This is just one example of how school libraries can be better utilised. Senior management and teachers of all subjects can work with their school libraries to improve students’ information and literacy skills.

How can teachers utilise their school library more effectively?

- Collaborative planning between teachers and school libraries is essential. The school librarian can also be an educator and ‘Library lessons’ do not have to be restricted to reading. These lessons can be handed over to school librarians to deliver an information literacy course.[5]

- The school librarian can also help to teach students about the inquiry process for any subject area. They can assist students in finding content—information and media—and support students through the crucial exploration stage.

- Source resources that are specifically created for students to use in their school library. For example, Sense about Science have created a free resource that encourages students to explore claims they encounter – online, in the news, in advertising, or among their friends – using evidence to evaluate them. You can download this resource here.[6]

- Teachers can liaise with their school library to ensure that they have department reading lists so that they stock the library with resources – both physical and digital – accordingly.

[1] A. W. Aldrich, ‘Following the Phosphorous Trail of Research Library Mission Statements into Present and Future Harbors: Sailing into the Future – Charting our Destiny’, ACRL 13th National Conference, Baltimore, MD, March 29-April 1, Chicago: Association of College & Research Libraries, 2007), pp. 304-316.

[2] European Commission, ‘Fake News and Disinformation, 2018’, Available: <https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2183> Accessed: 25 November 2021.

[3] Barry K Beyer, Critical Thinking, (Bloomington: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, 1995), p.33.

[4] Anon., ‘Critical Thinking: Where to Begin?’, The Foundation for Critical Thinking Online, Available: <http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/critical-thinking-where-to-begin/796> Accessed: 25 November 2021.

[5] L. B. Wehmeyer, The School Librarian as Educator, (Colorado: Libraries Unlimited, 1976).

[6] Sense About Science, ‘Evidence Hunter Activity Pack’, Ask for Evidence Online, Available: <https://askforevidence.org/articles/evidence-hunter-activity-pack> Accessed: 25 November 2021.