Adapted from an article, partially written by Sean Boret, Eton’s Strength and Conditioning Professional. The full article by Till et al. (2021) can be read here.[1]

Here at Eton, all boys are encouraged to take advantage of the Athlete Development Programme (ADP) and to use our dedicated ADP gym, regardless of the sports they like to play or the level at which they play them.

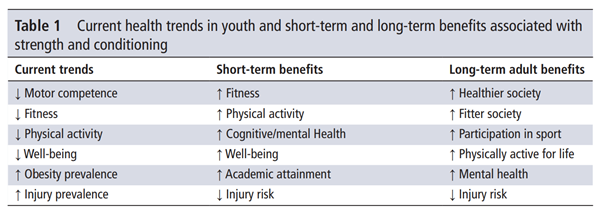

However, this is not the norm. According to a study conducted by Sandercock and Cohen (2019), levels of physical of activity and fitness in youths are in decline, a trend which has only been worsened by COVID-19.[2]

The World Health Organisation recommends 60 minutes per day of physical activity for young people with an additional three days of muscle and bone conditioning per week. However, the rise in youth obesity levels suggests that these recommendations are not always being met, especially in regards to strength and conditioning.

Till et al. (2021) argues that through physical education (P.E.), extracurricular activities and sport, schools provide the most suitable context in which to support the WHO’s recommendations and to facilitate strength and conditioning activities in particular.

Through Eton’s ADP, pupils are able to develop their overall athletic performance, including: an appreciation of health nutrition, the importance of rest and recovery, and how exercise can have a positive impact on mental health.

Perceived Barriers

However, Till et al. (2021) also argues that, in a number of schools, there are several barriers which can prevent strength and conditioning activities from being prioritised. These include:

- A perceived lack of value and misunderstanding of promoting health through skill-related components of physical fitness.

- A tendency for youth activities to focus on sport-specific skills and competition.

- School timetabling implementing ‘health and fitness’ at limited time points each year focusing instead on games and sport-based curricula rather than year-round aerobic and strength-based activities.[3]

This is exacerbated by the fact that there is often a lack of awareness of the relationship between motor skill and strength building activities and positive health outcomes; the misconception that participation in games or sports-based curricular activities alone ensures suitable development of strength and neuromuscular skills, and the fact that many schools do not have access to qualified coaches or suitable equipment.[4]

Potential Solutions

Indeed, at Eton, there are ADP gym sessions six days a week. However, for a joined-up approach, it is essential that schools ensure that strength and conditioning forms part of a whole school ethos.

The study by Till et al. (2021) supports this, recommending that the main way to overcome these barriers is to ensure the integration (and not just the addition) of strength and conditioning within P.E. and extracurricular activities.

Examples of this may include:

- Early exposure to movement skills and muscular strength development in childhood to facilitate early neural responsiveness to motor skill and resistance training.

- The implementation of regular strength and conditioning activities within warm-ups as part of P.E. lessons and sports games.

- The design and implementation of small-sided games to concurrently develop aerobic fitness.

- The implementation of an appropriate and progressive resistance training programme, both within and outside of the school timetable.

Strength and Conditioning Practitioners

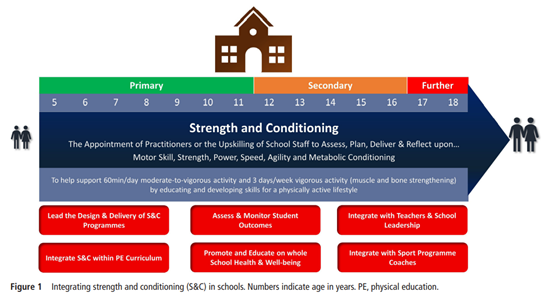

Till et al. also advocate the appointment of dedicated Strength and Conditioning Practitioners within schools.[5] Figure 1 provides an overview of how Strength and Conditioning Practitioners could be integrated [NJ-J1] within a school and their key roles.

Acknowledging the contextual, leadership and curriculum restrictions placed on schools, Till et al. (2021) suggest that Strength and Conditioning Practitioners can be integrated effectively in the following ways:

- Strength and Conditioning Practitioners should aim to support and integrate the key [NJ-J2] principles through a variety of curricular streams (i.e. P.E., afterschool programmes). To achieve this, schools should consider employing qualified individuals with relevant experience and knowledge of working with young people.

- Strength and Conditioning Practitioners should try to enhance the knowledge base and skills of school staff in recognising the benefits of strength and conditioning and in supporting students. This could be achieved by providing continued professional development opportunities for school staff.

[1] Kevin Till, A. Bruce, T. Green, et al., ‘Strength and Conditioning in Schools: A Strategy to Optimise Health, Fitness and Physical Activity in Youths’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2021), Available: <doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104509> Accessed: 30 September 2021.

[2] G.R.H. Sandercock and D.D. Cohen, ‘Temporal Trends in Muscular Fitness of English 10-year-olds 1998-2014: An Allometric Approach’, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, (2019) Vol. 22, pp. 201-205.

[3] J. Baker, Integrate Strength and Conditioning into the PE Curriculum at Secondary School’, The Journal of Strength and Conditioning, (2015), Vol. 38, pp. 27-35.

[4] .F. Bergeron, M. Mountjoy, N. Armstrong , et al., ‘International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement on Youth Athletic Development, British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2015), Vol. 49, pp. 843-851.

[5] C.J Bishop, P. McKnight, C. Alexander, et al., ‘Advertising Paid and Unpaid Job Roles in Sport: An Updated Position Statement from the UK Strength and Conditioning Association, British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2019), Vol. 53, pp.789-790.