Jonathan Beale, Researcher-in-Residence, CIRL

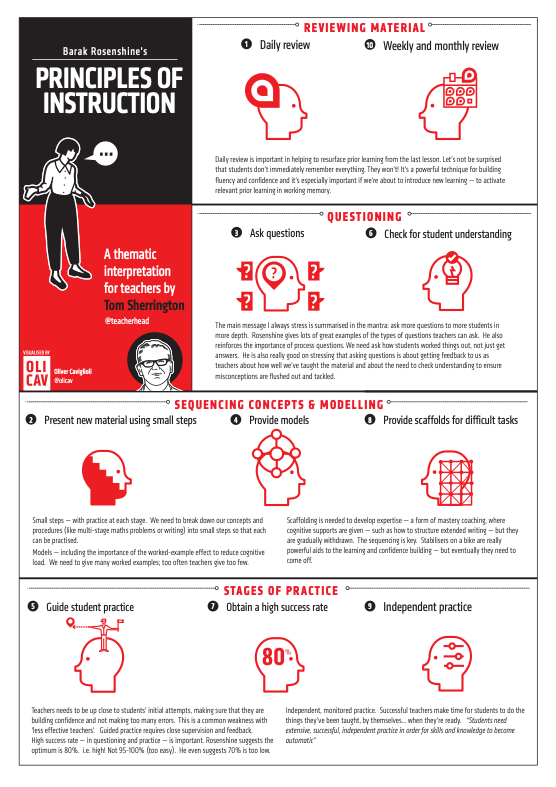

Our blog last week offered a brief introduction to Barak Rosenshine’s influential ‘Principles of Instruction’ and Tom Sherrington’s division of Rosenshine’s principles into four ‘strands’, in his book, Rosenshine’s Principles in Action. Sherrington uses the strands to explain Rosenshine’s principles, by connecting the principles with those to which they bear the closest relations, illustrating how the principles complement and support one another, and offering practical advice for their implementation, in addition to that offered by Rosenshine. This week’s blog post explores Sherrington’s strands and Rosenshine’s principles in more detail.

Let’s first recap Rosenshine’s ten principles. Below is the name Sherrington gives to each principle, followed by the way Rosenshine expresses each principle in ‘Principles of Instruction’ (all page references are to that article):

1. Daily review

‘Begin each lesson with a short review of previous learning: Daily review can strengthen previous learning and can lead to fluent recall’ (p. 13).

2. Present new material using small steps

‘Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step: Only present small amounts of new material at any time, and then assist students as they practice this material’ (p. 13).

3. Ask questions

‘Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students: Questions help students practice new information and connect new material to their prior learning’ (p. 14).

4. Provide models

‘Providing students with models and worked examples can help them learn to solve problems faster’ (p. 15).

5. Guide student practice

‘Successful teachers spend more time guiding students’ practice of new material’ (p. 16).

6. Check for student understanding

‘Checking for student understanding at each point can help students learn the material with fewer errors’ (p. 16).

7. Obtain a high success rate

‘It is important for students to achieve a high success rate during classroom instruction’ (p. 17).

8. Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks

‘The teacher provides students with temporary supports and scaffolds to assist them when they learn difficult tasks’ (p. 18).

9. Independent practice

‘Require and monitor independent practice: Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic’ (p. 18).

10. Weekly and monthly review

‘Engage students in weekly and monthly review: Students need to be involved in extensive practice in order to develop well-connected and automatic knowledge’ (p. 19).

Rosenshine’s ten ‘Principles of Instruction’, by Oliver Caviglioli

Each of Sherrington’s strands contains two or three of Rosenshine’s principles. Sherrington argues that these four strands run throughout all of Rosenshine’s principles:

Strand 1: Sequencing concepts and modelling (principles 1 and 10)

Strand 2: Questioning (principles 3 and 6)

Strand 3: Reviewing material (principles 2, 4 and 8)

Strand 4: Stages of practice (principles 5, 7 and 9)

Sherrington provides a succinct overview of the strands in a blog post in which he argues that Rosenshine’s ‘Principles of Instruction’ is ‘THE must-read for all teachers’. The following discussion draws upon that blog post. The illustrations below are taken from the useful poster above, by Oliver Caglioli.

Strand 1: Reviewing material

Reviewing material: Sherrington’s first strand, involving Rosenshine’s first and tenth principles

This strand involves the first and tenth of Rosenshine’s principles: ‘Daily review’ and ‘Weekly and monthly review’. With both of these principles, Rosenshine draws upon research concerning working and long-term memory.

Rosenshine writes that review ‘can help us strengthen the connections among the material we have learned’ (p. 13). An idea Rosenshine emphasises throughout his principles is that recalling prior learning should ideally be automatic. ‘Automaticity’ is the stage where learning and practice has been undertaken such that recall is effortless, thereby freeing working memory capacity (p. 13). Working memory is the area of memory where we process information. It has very limited capacity and can only handle a few pieces of information at once (p. 13).

Automaticity requires ‘overlearning’: learning beyond the point of ‘initial mastery’, such that recall is automatic and skills are fluent (p. 13). ‘When material is overlearned’, Rosenshine writes, ‘it can be recalled automatically and doesn’t take up any space in working memory’ (p. 18).

The free space in working memory helps us to perform other tasks, such as learning something new. Our working memory is limited; if we use much of it for recalling what we have learned, we have less available to engage in other mental activities important to learning. ‘The available space can be used’, Rosenshine writes, ‘for reflecting on new information and for problem solving’ (p. 19).

Daily review supports the process of building up the amount of effective practice required to reach the level of mastery where recall is automatic. Rosenshine writes that thousands of hours of effective practice are required to reach this level (p. 13).

Sherrington writes that the first principle is important for recalling learning from the previous lesson. Activating relevant prior learning in the working memory is particularly important when teachers wish to introduce new learning. Sherrington suggests that daily review is also important for developing students’ fluency and confidence in a subject.

Rosenshine’s tenth principle concerns the retrieval of learning in the long-term. It involves the development of long-term memory to support learning. The effort involved in recalling recently learned material helps to embed it in long-term memory. The more often we do this, the greater ease we have when we try to connect any new material we learn with our existing knowledge.

Strand 2: Questioning

Questioning: Sherrington’s second strand, involving Rosenshine’s third and sixth principles

Sherrington connects the third and sixth of Rosenshine’s principles, ‘Ask questions’ and ‘Check for student understanding’. Rosenshine’s research showed that ‘more effective teachers’ – i.e., teachers whose classrooms made the highest gains in standardised achievement tests (p. 12) – ‘spent more than half of the class time lecturing, demonstrating and asking questions’ (p. 14). They demonstrated by, for example, modelling successful answers or ways to complete tasks, by demonstrating how they should be done, and asking students questions. ‘Modelling’ is an instructional strategy where a teacher demonstrates a new concept or approach to learning and students learn through observation. Asking students the right kinds of questions has the benefit of giving teachers an idea of how successfully material has been learned, hence the link Sherrington draws between the first and sixth principles.

Sherrington writes that the purpose of checking understanding is to ensure that any misconceptions concerning the material learned have been addressed. Sherrington summarises this strand with the recommendation that teachers ask more questions to more students in more depth.

A question lacking depth would be a broad, closed question, such as, ‘Is that clear?’ or ‘Does everyone understand?’. While such questions can be addressed to all students, they don’t help a teacher to figure out what, exactly, might not have been understood, nor by whom.

Among the kinds of questions Rosenshine argues teachers should ask students are ‘process questions’: questions about the process of learning – e.g., how a student worked something out (contrast, for example, with factual questions). Asking questions is also important for teachers to receive feedback about how well material has been taught. Rosenshine writes that more effective teachers asked ‘students to explain the process they used to answer the question, to explain how the answer was found’ (p. 14).

Strand 3: Sequencing concepts and modelling

Sequencing concepts and modelling: Sherrington’s third strand, involving Rosenshine’s second, fourth and eighth principles

Rosenshine’s second principle emphasises the importance of learning material in small steps, given the limited capacity of our working memory. This draws upon psychological research concerning ‘cognitive load’, a good definition of which is the following, by Frederick Reif:

‘The cognitive load involved in a task is the cognitive effort (or amount of information processing) required by a person to perform this task. If the cognitive load needed for learning becomes excessive, little or no learning can occur’.[1]

To avoid cognitive overload, Rosenshine argues that teachers should present information in small steps and only proceed to the next step once the previous steps have been mastered.

Mastery requires a great deal of practice; so, there needs to be sufficient practice at each step. Where possible, complex concepts, theories, procedures, methods and pieces of knowledge need to be broken down into simpler ones, each of which can be practised as a student develops their understanding of the more complex area to be learned. Rosenshine calls this ‘mastery learning’: ‘a form of instruction where lessons are organized into short units and all students are required to master one set of lessons before they proceed to the next set’ (p. 17). He reports that more effective teachers ‘presented only small amounts of material at a time’ (p. 16) and taught in small steps with sufficient practice given to each step before proceeding (p. 17).

Modelling helps with learning by, for example, helping students see how to solve problems or structure essays. Modelling complements the second principle because it can help to clarify the specific steps involved in learning. Modelling can be carried out by, for instance, the use of ‘worked examples’: a form of modelling where a teacher provides ‘a step-by-step demonstration of how to perform a task or how to solve a problem’ (p. 15). Rosenshine argues that the most effective teaching involves many worked examples.

‘Scaffolds’ are temporary instructional supports used to assist learners, which should be gradually withdrawn as students gain competency (p. 18). Modelling can function as a form of scaffolding, as can teaching methods such as the teacher thinking aloud. ‘Thinking aloud’ is a form of scaffolding where a teacher shows the thought processes they go through as they undertake a task which students need to learn how to perform themselves (p. 18).

The idea behind scaffolding is that ‘cognitive supports’ are provided and are gradually withdrawn as a student gains competency. In this way, scaffolding can help to develop a student’s expertise and mastery in a subject. Rosenshine writes that thinking aloud is an example of ‘effective cognitive support’ (p. 15).

Sherrington writes that the three stages outlined in the three principles summarised in this strand provide ‘a superb guide’ on ‘how to sequence knowledge’. The process of sequencing can aid the process of gradually removing the scaffolds, hence the connection between the second and eighth principles. The connection with the fourth principle is that modelling is a form of scaffolding and can support the process of moving through the sequence of steps involved in learning.

Strand 4: Stages of practice

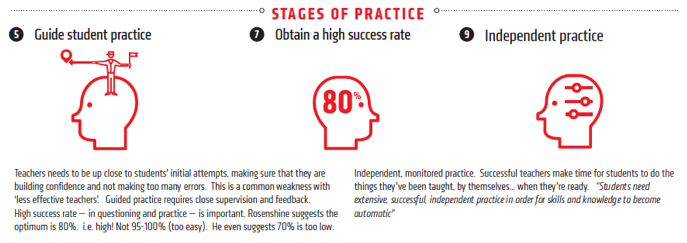

Stages of practice: Sherrington’s fourth strand, involving Rosenshine’s fifth, seventh and ninth principles

Rosenshine’s fifth principle states that teachers should build more time into lessons for guided student practice of the tasks and material learned. Rosenshine observes that more effective teachers do this. Practice is required to store what is learned in long-term memory; the best form of guided practice is that which is guided by an expert.

Sherrington writes that guided practice involves close supervision and feedback from teachers. Teachers need to observe students’ attempts to learn and complete tasks, to ensure that they build confidence and do not make too many errors.

Rosenshine’s seventh principle holds that teachers should strive to obtain a high success rate in questioning and practise exercises with students. Rosenshine writes that a success rate of 80% ‘shows that students are learning the material, and it also shows that the students are challenged’ (p. 18). A success rate much higher than this would suggest a lack of stretching and challenging. If a teacher were, for example, setting class tests and the whole class were regularly scoring 95-100%, the teacher should make the tests harder, to ensure the class is sufficiently stretched and challenged. But if the success rate is too low, it suggests the class is making too many mistakes.

Rosenshine suggests that a success rate of around 70% is too low. In the only issue he raises with Rosenshine’s principles, Sherrington suggests that we shouldn’t worry too much about the precision here; we might find that a lower success rate is in fact optimum.

Rosenshine also writes that the most effective teachers taught material ‘in small steps followed by practice’, indicating the connection Sherrington observes between this principle and the fifth principle. Here we can also see a connection with the second principle, ‘present new material using small steps’.

The ninth principle, ‘independent practice’, involves students practising tasks without guided practice from the teacher. While independent, this practice should be monitored, to ensure that mistakes are not made – e.g., a teacher checking the work a student has completed during independent practice.

Rosenshine argues that independent practice is required for overlearning and automaticity. This is the stage of practice we should be aiming for as teachers with our students. ‘Students need’, Rosenshine writes, ‘extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic’ (p. 18).

In the blog post discussed above, Sherrington writes that Rosenshine’s principles provides ‘the best, most clear and comprehensive guide to evidence-informed teaching there is’. Among the reasons Sherrington offers for why all teachers should read Rosenshine’s ‘Principles’ are that it ‘resonates for teachers of all subjects and contexts’, ‘because it focuses on aspects of teaching that are pretty much universal’, including ‘questioning, practice [and] building knowledge’; it ‘makes direct links from research to practice’; it ‘does an excellent job in helping teachers to link practice to cognitive psychology’, through, for example, Rosenshine’s ‘references to ideas about memory and cognitive load theory’; and the research ‘is often based on linking classroom observations to student outcomes’.

Sherrington offers two important pieces of advice on how to best engage with Rosenshine’s principles:

- First, don’t turn it into a checklist – e.g., principles to be ticked off during lesson observations. Sherrington emphasises that Rosenshine’s ‘Principles of Instruction’ is ‘a guide for professional learning’, rather than ‘a ticklist for accountability’.

- Second, explore the implications of each principle at a subject-specific level. The principles and the strands into which Sherrington divides them need to be contextualised for successful implementation and applicability. They ‘have meaning’, Sherrington writes, ‘only in the context of curriculum content’.

[1] Frederick Reif, Applying Cognitive Science to Education: Thinking and Learning in Scientific and Other Complex Domains (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), p. 361. On applying cognitive load theory in the classroom, see D. Shibli and R. West, ‘Cognitive Load Theory and its Application in the Classroom’ (Impact, February 2018).