Student engagement is one of the most important factors in effective teaching and learning. One of the greatest challenges posed by distance learning is how to engage students remotely. Teaching is an interactive, interpersonal process which involves reading the subtleties of human behaviour as indicators of how successful learning has been. A classroom provides a social environment where teachers can read and respond to student behaviour immediately; an online teaching environment is only a substitute for the classroom. This post offers three suggestions for engaging students when teaching online. (For general advice on effective distance learning, see last week’s blog post.)

Jonathan Beale, Researcher-in-Residence, CIRL

1. Foster an online community through several forms of teacher presence

A class is an intellectual and social community; classroom environments foster intellectual and personal bonds between students and between the teacher and the class. Such bonds and the kinds of interaction facilitated in the classroom can also be facilitated online, by fostering an online community, imitative of the classroom community.

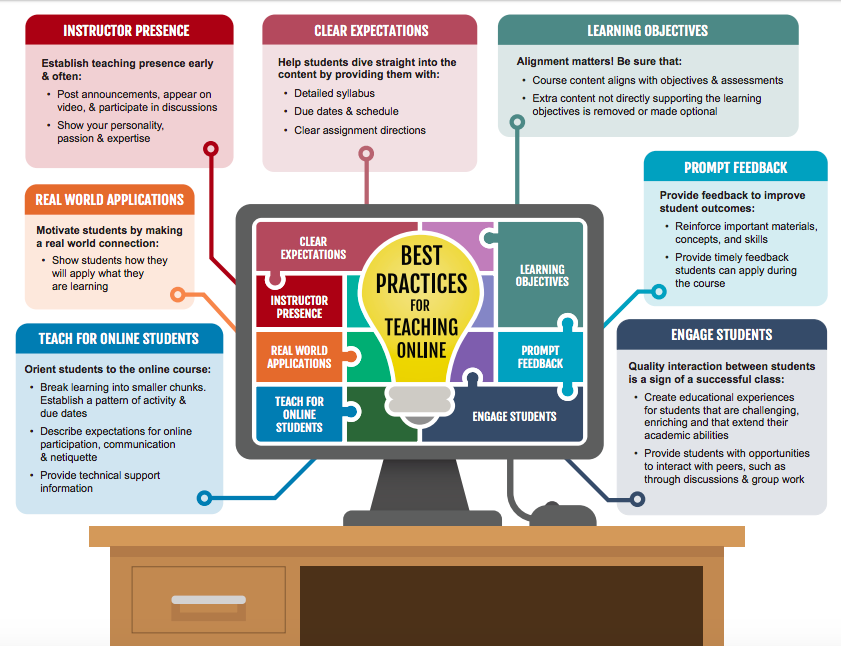

In their Stanford University article on the ‘Ten Best Practices for Teaching Online’, Judith Boettcher and Rita-Marie Conrad emphasise the importance of fostering a community when teaching online.[1] They recommend teacher presence as the most effective way to do this:

‘The same type of community bonding happens in an online setting if the faculty presence is felt consistently. Regular, thoughtful, daily presence shows the students that the faculty member cares about who they are, cares about their questions and concerns, and is generally present for them to do the mentoring, guiding and challenging that teaching is all about.’

Presence can be felt in many ways; teacher presence doesn’t mean that the teacher needs to be available 24/7. Indeed, it’s important to set realistic expectations on the hours that the teacher is available for communication and not to create unrealistic expectations of availability (teachers wouldn’t be available 24/7 in school). While online teacher presence is most immediately felt through media such as videoconferencing, web chat and email, teachers can utilise other means of generating presence to provide a convivial online teaching and learning community.

Video, audio and text presence all ‘compensate for the physical remoteness of online learning and the lack of face-to-face presence’. Video clips of teaching a topic or explaining a task, or audio feedback on work contribute towards the feeling of teacher presence. These are among the ways an online community can be fostered.

2. Imitate the classroom environment as best as possible, but don’t try to replicate it

You cannot replicate a classroom environment, but you can imitate it – writes Satesh Bidaisee, Professor of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at St. George’s University, in Jean Dimeo’s 2017 article ‘Take My Advice’, which offers tips for teaching online from 17 instructors experienced in online teaching. Imitating the classroom helps to foster an online community, which itself is an imitation of the classroom community. But engagement needs to take a different form online than in the classroom, because ‘online habits of interaction are differently habituated than in the classroom’, writes another contributor, Tom Beaudoin, Associate Professor of Religion at Fordham University.

It’s important to imitate some of the useful aspects of classroom teaching, because the classroom affords an environment conducive to effective teaching and learning and is the normal learning environment for students. Perhaps most importantly, a classroom affords an environment where student engagement can be easily encouraged.

There are many online platforms that offer functions to imitate some of the teaching and learning facilities offered in the classroom. Collaborative documents can be completed in real-time with programs such as Microsoft OneNote and Google Docs, imitating the kinds of collaborative group work that can be completed in person. Videoconferencing programs such as Zoom offer the facility for creating breakout rooms, where students can work in groups. Students could also be encouraged to set up their own virtual discussion groups with one another to share ideas.

Bidaisee writes that the ‘more direct involvement your students have in the course, the more invested and productive they will be’. Live videoconference classes, student discussion forums, opportunities for students to raise questions to one another and to the teacher, student videoconference presentations and collaborative documents all contribute towards imitating the classroom environment in a direct and interactive way. Such activities enable students to interact with the teacher and with one another online in similar ways to how they would interact in a classroom. Activities like these can help foster an online community.

3. The longer distance learning continues, the more important teacher-student contact becomes

In a recent blog post on ‘Setting work for a long-haul shut-down’, Tom Sherrington offers useful advice on engaging students through distance learning. Perhaps his most important piece of advice is: the longer distance learning goes on, the more important personal teacher-student contact becomes.

During school terms, students’ levels of focus, concentration and motivation sway. Distance learning faces the same difficulty. But, additionally, students need to feel connected through online facilities during a long period of time away from the school environment, their school friends, teachers and tutors. Regular contact helps maintain the online community.

Videoconferencing, email and the chat functions on videoconferencing programs offer means of regular communication with all students in a class. As outlined in last week’s blog, some programs offer straightforward forms of communication that function as easy substitutes for email and are not a significant departure from the familiarity and ease of email. For example, Microsoft Teams has a ‘chat’ function which offers a useful and effective means of communicating with students.

To maintain regular contact through other means, Sherrington recommends circulating tasks and resources regularly rather than several weeks of tasks at once. But if several weeks of tasks are circulated in one go, the teacher can check up on students at regular intervals – for example, to ‘prompt students as to where they should be at any given point’. Sherrington also recommends actions such as recording video clips, to keep students engaged as members of an online community.

As time goes on in distance learning, teacher-student contact becomes more important. At some point, students may experience distance learning fatigue. This can be alleviated by maintaining regular contact with students and mixing up the kinds of tasks and activities they are given. Just as we have to mix up tasks and activities in the classroom to maintain student engagement and motivation, and just as this becomes increasingly important and difficult as time passes during a term and students become fatigued, we need to do similar things online.

Teacher-student contact is also particularly important during the early stages of distance learning. Sherrington updated his blog post based on feedback he received from several schools, with a note that ‘setting up a system to contact every student within the first couple of weeks is essential – just to make sure they’re ok and can access the work’.

[1] Originally published as the third chapter in J. V. Boettcher and R-M. Conrad, The Online Teaching Survival Guide: Simple and Practical Pedagogical Tips (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010).