This week’s blog post is by Kayleigh Betterton, teacher of English at Eton College. Kayleigh was previously the Research Lead at Bedford School and is now working on her PhD in English at the University of London.

I am sure I am not alone in feeling a sense of apprehension at the idea of overhauling an entire curriculum in place of one that centres around project-based learning (‘PBL’). And yet, a small part of me also feels that any institution willing to take such a risk deserves my respect.

The Drew Charter School in Atlanta, Georgia, is that school. Drew opened in 2000 and serves approximately 1,800 students from the East-Lake area of Atlanta. Instead of following the traditional curriculum, Drew’s students learn entirely via PBL.

There is an emerging evidence-base on the effectiveness of project-based learning, but the extent of its effectiveness in the UK school system has not yet been fully explored. I wanted to see for myself whether this approach was truly as effective as its advocates claimed and in 2018, I was fortunate enough to visit Drew and see PBL in practice.

Here is what I learned.

What is project-based learning?

The Buck Institute for Education defines PBL as:

‘A teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge.’[1]

However, PBL is not part of some new teaching craze, nor does it set out to reinvent the wheel. It first gained popularity at the beginning of the twentieth century when it was defined by John Dewey as ‘learning by doing’ in his work Education and Democracy (1916).[2]

If we reflect on our own teaching practice, it is likely that many of us have set project work that emphasises ‘learning by doing’ in one form or another.

Indeed, over the last couple of months, a number of my colleagues have set their classes project work for asynchronous lessons. In theatre studies, for example, students have been working on Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible (1953) and year 10 students have undertaken a project about witchcraft where they are required to make poppets.

What turns project work into project-based learning?

Project work is often characterised by being short and, at times, intellectually-light, designed to complement traditional teaching methods. PBL, on the other hand, is predominantly used as the only vehicle for teaching the knowledge and skills students need to learn.

In recent years, PBL has experienced a revamp which has been characterised by an increase in the use of digital technology and a renewed focus on academic rigour.[3] In 2015 for example, California’s Buck Institute of Education published their ‘Gold Standard’ criteria in an attempt to formalise PBL and they encourage schools to adhere to this when setting projects.[4]

What is the link between project-based learning and motivation?

It has been argued that one of the primary benefits of PBL is the impact it has on raising student motivation. The American teaching collective ‘Thoughtful Learning’ state that the reasons for this are:

- students gain autonomy;

- classrooms become collaborative communities;

- students work on real-world projects;

- teachers are forced to provide constructive feedback;

- students get up and move;

- projects present challenge and rigour;

- students are given space to fail.[5]

As we saw in an earlier blog post, motivation is an essential part of character education and can help to increase well-being and academic attainment.

I would argue that for students to feel motivated, it is important that they feel a sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Teachers can foster motivation by linking learning to the bigger picture: that is, encouraging students to think about how what they are learning links with other areas of their learning and their own lives.

What does project-based learning look like in practice? The Drew Charter School

When you visit Drew Charter School, it is immediately apparent from the moment you set foot inside the building that PBL informs every aspect of the school’s design and function. Project work is displayed throughout the building and the central hub of the school consists of large breakout spaces where students can work together.

Drew claims that equity is at the centre of their approach to education and they argue that PBL is the best way to achieve this. Drew’s website states that PBL is,

‘an approach to learning content standards that makes learning more engaging for students, while promoting equity in learning the curriculum. Students construct their own answers and innovative solutions to challenging, authentic, driving questions that meet real world needs in our community.’

Drew proceeds to describe some of the benefits of PBL:

‘[PBL] gives students more opportunities to have increased voice and choice in how they learn while gaining a deeper understanding of their content. Students also have opportunities to collaborate with community partners and in-field experts to learn new skills, receive feedback, and even create solutions as they engage in PBL.’[6]

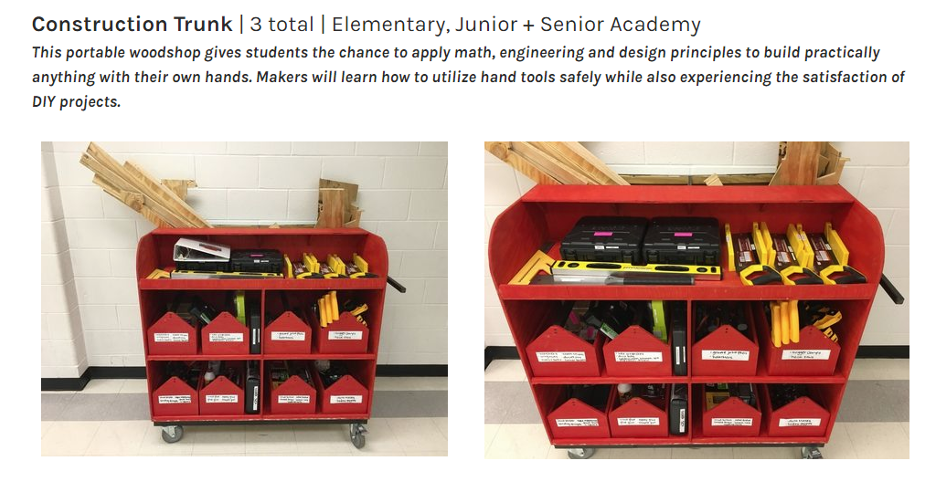

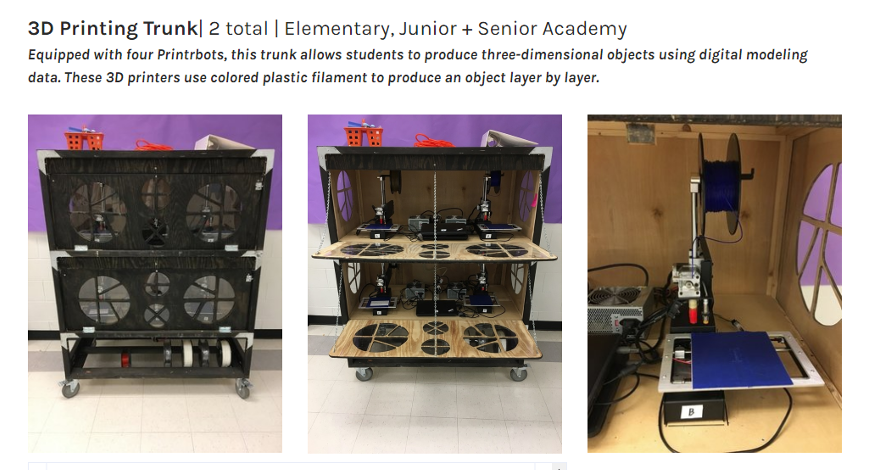

Unlike traditional schools, at Drew there are no departments, per se, only ‘Project Collectives’. According to the school’s Principal, these change each year depending on which projects are being carried out and which subjects are working together. For example, you may have a drama, English and history collective working on a project one year and they would be situated in a project hub together to plan lessons collaboratively. Resources and materials are then brought to classrooms via ‘Trunks’, depending on the nature of the project.

It was refreshing to visit a school brave enough to overhaul their curriculum and replace it entirely with a PBL model. Indeed, the school certainly had an exciting and innovative feel around the place and students appeared highly motivated, even continuing to work on their projects over their lunch breaks. I wondered how I could incorporate this approach within my own teaching practice in a way that would not require a complete overhaul of the curriculum.

An experiment in project-based learning: Bedford School, UK

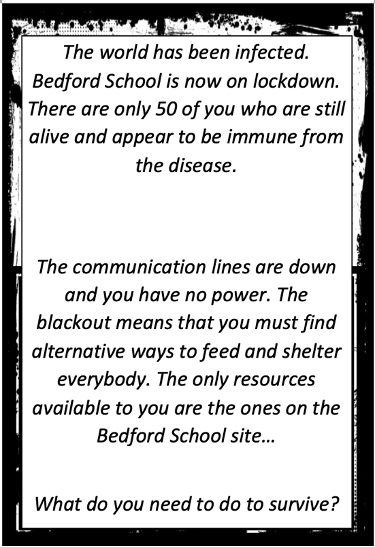

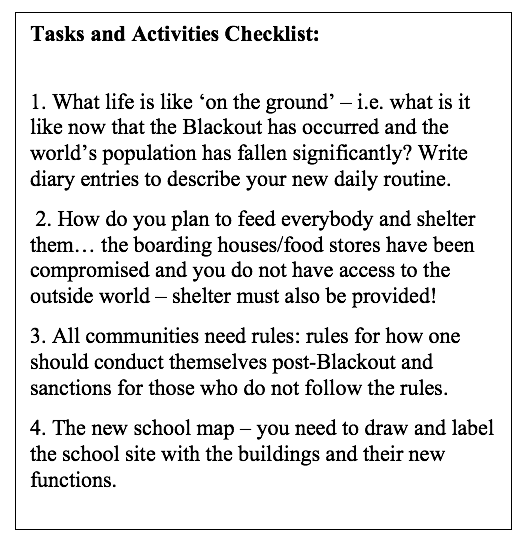

Upon my return to the UK, I attempted to integrate PBL into my teaching at Bedford School. The project focused on two Year 9 English modules: ‘Dystopian Fiction’ and ‘Creative Writing Skills’. I designed a project that required my students to research and create a ‘survival guide’ for their fellow classmates. It had to include the following:

Cross-curricular links

All project tasks needed to be submitted via a WordPress blog and the computer science department helped by providing guidance to the students on how to design and create blogs. Although some found this challenging at first, the students soon became proficient in designing content for their blogs and, in most cases, the finished product featured embedded YouTube videos, and widgets and posts were ‘tagged’ accordingly.

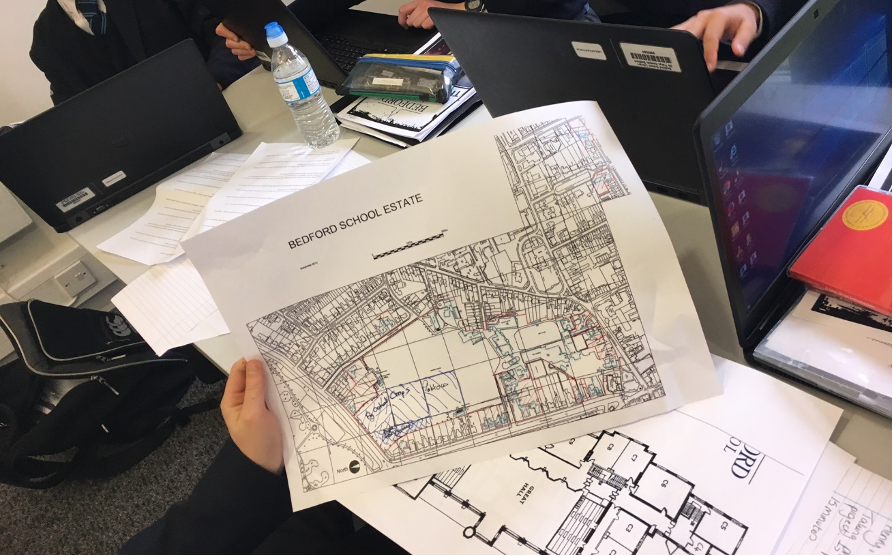

Another task required students to redesign the school’s layout. This meant that students had to contact the school’s Buildings and Site Team for a scaled map of the school grounds. Some groups took the extra step and also spoke to the Design and Technology Department, who provided them with computer-aided design software so they could redesign the map to scale.

The students had to draw upon the skills they had gained from all areas of their education, not just from the classroom. The CCF department were invaluable in helping the students with their second activity: how to feed and shelter the community. They provided guidelines on how to build make-shift shelters and advice on what could be foraged safely. Some groups even ended up writing recipes for mouse and fig stew (!) based on their discovery of mature fig trees dotted around the school site.

Was this project effective in raising motivation levels?

In the aftermath of the project, students were asked to complete a questionnaire about their experiences of the project. Although mostly anecdotal, there were some interesting trends which emerged. Students expressed comments such as:

“It allows us to spend several weeks working up to an end result that we are truly proud of.”

“My favourite lessons were when we were split into groups and had various different problems to solve about the subject we were learning about. I enjoyed it because it forced my group to look at the subject in different ways and think about it more and it was really fun because it was a new way to think about the subject.”

“The independence and freedom to do our own thing created a very enjoyable project, and a sense of pride at the finished result.”

“Practical activities made the lessons more interesting because it gets you on your feet and moving around which I find makes me concentrate more. Group research topics also helped because it allowed us to do research on the topics we want to cover.”

As you can see from the phrases emphasised above, students tended to comment on the autonomy and sense of ownership they felt they gained from the project. By allowing students to choose the way in which they approached tasks, the learning was personalised and subsequently made more significant to the learner. Evidence from psychology suggests that personalisation tends to have a positive effect on the intrinsic motivation levels of learners and as their teacher, I was impressed with the level of engagement I saw from students.

Strategies for effective project-based learning

The key to successful PBL lies in the planning. Designing projects not only requires a significant degree of preparation but it also requires teachers to work with other departments and to think ahead. When projects are designed effectively, they can enhance students’ existing skills, whilst also encouraging them to make links and connections to the skills they have gained from other subjects.

Here are my top five tips for effective PBL:

1. Dedicate substantial time and energy to planning the project. Whilst it’s important to give students the freedom to choose their own activities, some will need more guidance. Tasks can be scaffolded for less confident students.

2. Checklists and rubrics help to ensure that project-based learning is meaningful and utilises the skills required.

3. Think outside the box and encourage students to do the same. Award extra marks for innovative ideas.

4. Reach out to other departments to see if they can help provide subject-specific support and guidance.

5. Showcase students’ work and give them a platform to promote what they have achieved.

Further guides to using project-based learning

- The Innovation Unit, in conjunction with Learning Futures and High Tech High, have put together a free, downloadable guide for teachers entitled Work that Matters: The Teacher’s Guide to Project-based Learning.

- The Drew Charter School relied upon the ‘Gold Standard’ criteria set out by the Buck Institute of Education.

- See this earlier CIRL blog post on PBL.

[1] ‘What is PBL?’, Buck Institute of Education: PBL Works Online (2020).

[2] John Dewey, Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (New York: Macmillan, 1916).

[3] Innovation Unit, Work that Matters: The Teacher’s Guide to Project-based Learning (Paul Hamlyn Foundation, 2012).

[4] John Larmer, ‘Gold Standard PBL: Essential Project Design Elements’, Buck Institute of Education: PBL Works Online (2020).

[5] Thoughtful Learning, ‘Why Project-based Learning Motivates Students’.

[6] Drew Charter School, ‘Our Innovative Approach’.

[7] Drew Charter School, ‘14 Steam Trunks. 2 Campuses. Endless Possibilities for Making and Learning’, STEAM at Drew Charter Blog.